I’ve just been fascinated to learn that there was a “rock-cut flat grave”, probably interred in the 7th century AD, found in the early 1850s near Stoke-on-Trent. Specifically cut into red sandstone somewhat near the River Trent at Barlaston, now a large village on the south edge of Stoke-on-Trent. My thanks to Steve Booth of Stone for telling me of this. It’s possible I had read of it while writing my history of Burslem and the Fowlea Valley, which was many years ago now, but had then considered it a little ‘out of area’. Now the grave perhaps takes on a new significance in the light of the Staffordshire Hoard discoveries, so I thought a quick summary would be in order to save other people some time. Here’s what I was able to find via the Web, put into a rough order:

THE FIND:

The British Museum has a full summary account of the bowl and states that…

“The bowl fragments were found accidentally while planting trees on the Wedgwood estate in about 1850.” The find was written up by “Lawrence Wedgwood, FRGS, who had been present at the discovery [circa 1851], wrote a short report of the find, published in 1906 [when] Miss Amy Wedgwood caused an iron fence to be erected round the site of the grave to mark its position. […] An admirable account [of the bowl] was provided by Romilly Allen.

Allen adds a first-hand account had from Amy Wedgwood stating that the planting of the trees had been on… “the gravel-pit hill behind the house”. This confirms the location given in Lawrence Wedgwood’s paper (given in full, below).

THE GRAVE:

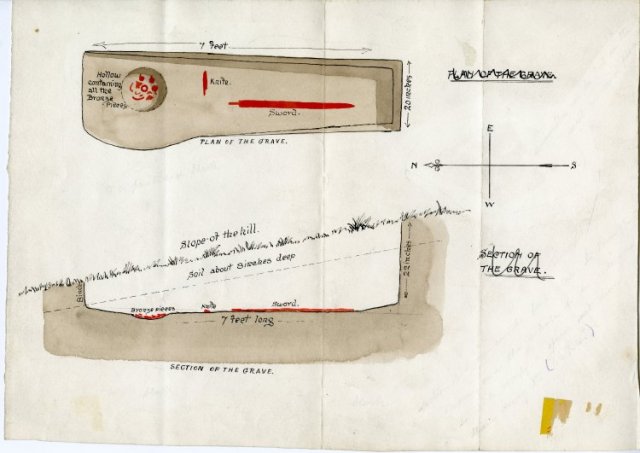

While the find was initially by workmen, it was very well documented considering the date was the 1850s. The burial was found along with a sword and a knife, the weapons indicating a male burial and very probably a warrior. The size of the 7-foot grave also indicates a male. The bowl was placed at the north end of the grave and found as bronze fragments in a depression. There was no trace of a barrow mound (tumulus) in the heavily ploughed land and no other graves were found nearby despite extensive tree-planting. The British Museum kindly offers a scan of the plan made for the site…

The grave was found without any trace of bones, and in the 1960s a cremation was mooted to explain their absence.

THE BOWL:

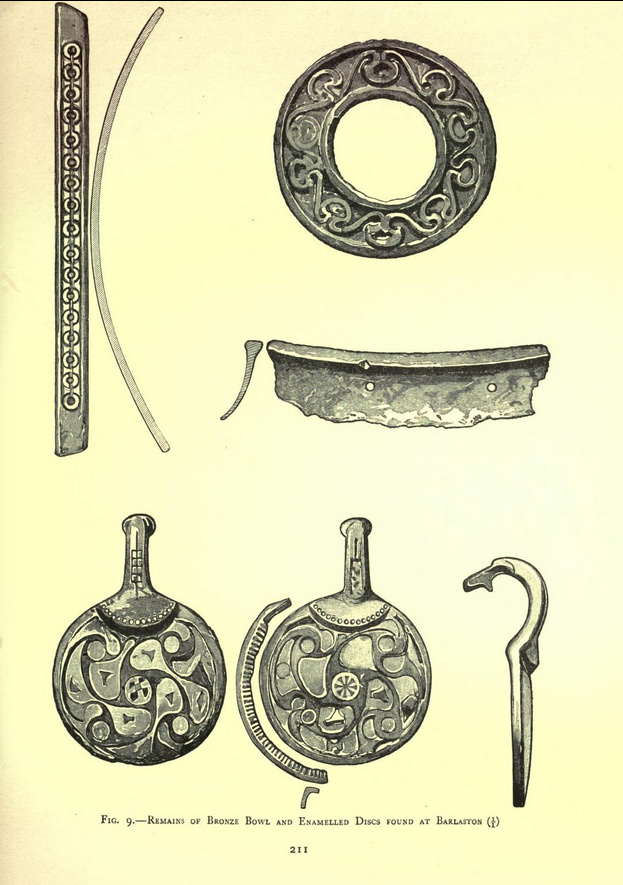

The book Roman and Celtic objects from Anglo-Saxon graves: a catalogue states that… “The vessel was found near complete”. The British Museum photography of the fragments of the bowl suggests such a phrasing is misleading to the layman, who may then expect to see the “near complete” shining bowl rather than fragments…

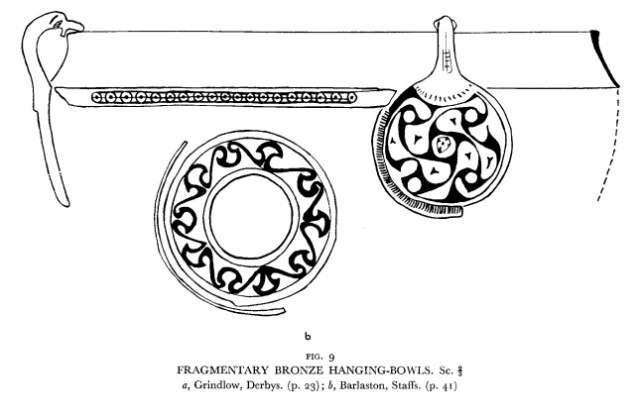

Ozzan also gives a line-drawing of the bowl’s reconstruction, confirming the fragmentary nature, and also notes that… “the bowl has been spun, not cast”.

The Victoria History of the County of Stafford also gives a good drawing (p.211) of the bowl…

Some Victorian antiquarians initially thought, wrongly, that the bowl fragments may have been from a helmet. Such as Llewellyn Jewitt in his Grave-mounds and Their Contents: A Manual of Archaeology, a book in which he also described the other fragments found in the Barlaston grave.

The Romilly Allen description is also online in open access, in a scan of Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. Although the illustrations of the disc designs appear to have been removed from the scanned Harvard library copy. Allen was of the opinion that the disc patterns were very early, reflecting the influence of late Celtic work. Ozzan later suggested an Irish influence (see quote below) on the discs via their enamelling.

DATING:

Audrey Ozzan in the article “The Peak Dwellers” is not entirely sure that the Barlaston bowl is 7th century, but is fairly sure…

“… the Barlaston bowl is of the simple type, but there are strong reasons for regarding it as seventh-century. Simple bowls from Faversham (Kent) and Hildersham (Cambs.) belong to a group which Haseloff places ‘in the first half of the seventh century and perhaps also in part of the sixth’; and the Hildersham bowl was associated with a shield-boss of seventh-century type. [… Though notes that the dating to the 7th century seems to be confirmed by] a recent paper suggesting that the Irish techniques of enamelling and millefiori found their way into English contexts by way of monastery workshops in England.”

SIMILAR BOWLS:

The Victoria History of the County of Stafford notes (p.210) three other bowls (perhaps of somewhat different dates) in nearby Dovedale in the Peak…

“Though an isolated burial the Barlaston discovery falls into line with others made just across the Derbyshire border. Remains of no less than three such bowls have been found in the neighbourhood of Dovedale: at Middleton-by-Youlgreave [an ‘east-and-west burial on Middleton Moor’], Over Haddon, and Benty Grange, the last lying in the grave beside the hair of a warrior, in association with a leather bowl ornamented with applied crosses. At Barlaston the bowl was found just where the head would have lain, and seems to have been in the centre line of the grave, so that perhaps the head rested within it at the time of burial.”

Audrey Ozzan’s article “The Peak Dwellers” notes that…

“only one Staffordshire barrow [that] affords an unequivocally seventh-century find. This is one of the barrows on the Cauldon Hills (Carrington, 1849), which contained an inhumation, sex and orientation unknown”

The latter find was by Thomas Bateman, recorded in his Ten Years’ Diggings in Celtic & Saxon Grave Hills (1861)…

“CAULDON HILLS. We afterwards opened a barrow on Cauldon Hills, in a lower situation than those before examined there. One-half had been removed down the level of the adjacent land…”

RECENT WORK and WIDER CONTEXT:

I note that there is a thesis on such English bowls by Jane Brenan, and from it the slightly revised book Hanging Bowls and Their Contexts: An Archaeological Survey (1991).

WHO WAS HE?:

Even by the mid 1960s Greenslade and Stuart’s A History of Staffordshire (1965) considered it rather a mystery in terms of its location and lack of immediate surrounding context…

“There is, however, one isolated burial at Barlaston, close to the [River] Trent south of Stoke, which has not yet been satisfactorily explained.”

Bury Bank and Saxon’s Lowe are fairly nearby. Bury Bank is associated with King Wulfhere (658-675 AD) and has never really been properly investigated. There might equally be some connection with Cauldon and the Peak. Given the isolation of the grave and the rough proximity to the river one suspects some liminal figure. Perhaps a long-serving guard or ferryman of the vital crossing of the Trent near Stone, who had made his home a little north at Barlaston. The site appears to be above a small tributary of the Trent, so one might imagine him skimming his coracle a short way down the tributary to reach the main Trent. Or possibly the uncontrolled flood-plain of the Trent made the river far wider at that time, making the tributary a significant inlet, and the burial site was indeed once effectively closer to the river.

WEDGWOOD’S PAPER:

L. Wedgwood, “Notes on Celtic remains found at the Upper House, Barlaston”, Transactions of the North Staffordshire Field Club (1906)

NOTES ON CELTIC REMAINS FOUND AT THE UPPER HOUSE, BARLASTON.

BY LAWRENCE WEDGWOOD, F.R.G.S.

Read November 23rd, 1905.

We moved from Etruria to this house in 1850, and it was soon after we came, that in planting the top of the hill to the east of the house, we came upon the grave in which the bowl, sword, and knife lay.

The house was built by my father on a plain grass pasture field, which had at some previous time been ploughed, and I never remember seeing any sign of a mound over the grave. One day, while the holes were being dug for planting, I found the labourers talking about some pieces of bronze they had found, and, wondering what it was, I mentioned this, and we then had the grave properly opened, and found the pieces portrayed on the accompanying sketches.

My brother, Mr. Godfrey Wedgwood, made a careful sketch of the grave and its contents, of which the sketches herewith are a correct copy.

The bronze bowl, I fear, had been shattered by the workman’s spade, but the sword lay along the side of the grave and the knife across it, the bronze bowl being, I presume, near where the head of the warrior lay (see sketch).

The sword broke into three pieces, and the knife also broke, on being lifted, being so badly rusted.

The bronze articles were in good preservation, except from the mischance of the bowl having been broken before we were aware of any grave being there. There were no bones and no cinerary [cremation] ashes, and no signs of any coffin.

Of course, being a shallow grave, and not air-tight or weatherproof, all signs of a skeleton had long since vanished.

At the date we found it, we presumed the bronze bowl to be a helmet, and the bronze handles of the bowl we thought were brooches, but other finds of recent years have led us to consider the bronze articles all part of bowl to contain the viaticum. [viaticum: heavenly meal, perhaps then understood as a sort of ‘pot of plenty’, and intended to sustain the deceased during their wandering voyage to find the halls of the afterlife]

Our grave seems to have been a solitary one, as in laying out all our garden and grounds and planting the wood to the east of the house, which would all cover five or six acres, we found no other graves, and although the top of the hill was a gravel pit when we came, and we used gravel largely from it, we found no other remains.

The hill is about 500 feet above sea level, and across the Trent, to the south-west, about two miles as the crow flies, lies the old British Camp [hill-fort] of “Bury Bank”, at the south end of Tittensor Common.

The grave is cut in the sandstone rock to some depth, and lies north and south; I presume, denoting its Pagan origin. My cousin, Mr. J. Romilly Allen, F.S.A., says the ornamentation of the bowl is distinctly late-Celtic, i.e., Pagan-Celtic of the Iron Age B.C. 300 to A.D. 450.

The form of the knife and sword, which are Saxon, however, point to a date at the end of the late-Celtic period.

The enamelled bronze discs were used as the handles of bowls, thus —

The discs were fixed to the sides of the bowls, and the hooks, which usually terminate in the head of a beast or bird, projected over the rim.

The curve of the pieces of the rim show that the diameter of the bowl was nine inches.

The curve of the ribs is the same, showing that they must have been fastened to the outside; but I don’t understand why the ends are sloping.

It looks as if they must have been placed diagonally, though how I cannot explain.

The metal is cast, not wrought, as is more usual, and the centre and marks on the bottom indicate that it must have been turned on a lathe. The enamelling of the discs and the designs arc of the Pagan-Celtic period.

The enamelling is exceptionally fine, as some of it is made, like Mille-fiore glass, by fusing several sticks of coloured glass together.

This bowl is of special value, because it is the only one that can be placed, beyond doubt, in the pre-Christian period.