Another fabulous green/wild man, from Germany circa 1480.

Monthly Archives: April 2017

Waterstones buzzes

I love the idea of Hive.co.uk where any book can be delivered to a local independent bookshop, and picked up in person from the shop. In practice it was easy and simple, bypassing all the inevitable hassle with big heavy parcels and couriers trying to deliver to a residential address where the outer door needs an entry-code.

I say “was” because, since the demise of my local indie bookshop, there’s now nowhere local to collect from. There is one local Hive affiliate left, but that’s up in the nearby moorland town of Leek. For me that might as well be on the Moon, in terms of the public transport connections and times. Not to mention the inevitable bus-sickness on two hours there-and-back. (‘How can it take that long to go ten miles’, you ask — ‘Welcome to North Staffordshire’s bus service’, I reply).

The city centre does still have a medium-sized Waterstones with a fairly humdrum stock, and it’s walk-able in terms of the distance. But I hadn’t even considered them as a Hive alternative until now. It turns out they do now offer a Hive-like collection service, via their online catalogue. They also offer something which Hive doesn’t, a wish-list. Bliss.

Delivery to the shop is free, too.

It turns out they have most, but not all, of the most important books I want. I’m happy to buy Kindle ebooks, of course. But there are many small scholarly publishers who use print-on-demand and offer no ebook edition.

Currently my local Waterstones can get, for instance…

However they’re light on some items. It’s difficult to believe, for instance, that J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator can have been allowed to go out of print and become unavailable in both paperback and hardback. How is that even possible? There’s also no listing of the University of Tampa’s vital book of key Lovecraft letters, O Fortunate Floridian: H.P. Lovecraft’s Letters to R.H. Barlow, still in-print. Some of the most recent Hippocampus Press titles are as-yet unlisted, but that’s probably because Hippocampus (or perhaps the POD printers Lightening Source) hasn’t yet uploaded the metadata to the world’s databases. It’s curious that the Disney book Before Tomorrowland is also missing, despite Amazon having it. Stover’s annotated The Time Machine: an Invention: A Critical Text is only “unavailable” as a hardback, where there’s a perfectly good in-print paperback available. They do however have a paperback of Arata’s The Time Machine – Norton Critical Editions.

Sadly they have the same jumbled and junky reviews as Amazon does — reviews which pertain to some other edition of the work rather than to the specific edition of it that you’re buying. Thus reviews of shoddy audiobooks get jumbled with reviews of ebook editions, and then these reviews are somehow supposed to ‘represent’ a fine annotated critical edition.

Anyway, Waterstones keep your shipment for 90 days at the shop, giving ample leeway for assemblage of a disparate order and then an in-person pick-up. Regrettably… “We do not currently accept National Book Tokens or paper gift vouchers online”. But it’s left unclear if they might accept book tokens for an in-person pickup, if (as with Hive.co.uk) one pays only on collection?

Sadly there’s no mention of accepting PayPal for a pre-paid order, so presumably they want a credit card. Big companies like this miss out on so many impulse buys, which would come if only they accepted PayPal. The same goes for Amazon’s Kindle ebooks.

I see there’s also a Waterstones Marketplace which links with Alibris for used books, but reading between the lines it looks like this is handled by the Alibris vendor and is thus ‘ship-to-the-home’ rather than ‘ship-to-the-store for 90-day collection along with your new books’. On a search for the missing Fortunate Floridian (see above) there was anyway no offer of a button to ‘Search on Marketplace’ for it.

Update: I see that eBay are now offering free shipping to and collection from your local Argos store (and Sainsbury’s, some of which have Argos inside them). It seems that all my local Argos and Sainsbury’s participate. And, of course, PayPal is accepted by eBay. This makes it a very interesting alternative to Waterstones (see above), though it seems it’s limited to the same set of new books and doesn’t extend to used books. The only downside would be that it would definitely be a less-cultured pick-up, re: waiting in the queue at a Stoke-on-Trent Argos.

Further update: no, it also extends to most used books a well, from large sellers. Wonderful! The only (fairly huge) problem there is that it is only kept for seven days inc. weekends. Compared to a much more sensible 90 days for Waterstones. For new books, it may be worth paying a premium of a few pounds at Waterstones in order to be able to collect at leisure, as and when.

Tolkien at Exeter College

John Garth profiles his Tolkien at Exeter College: Birth of a legend in his blog. A very good booklet as far as it goes, and the scholarship is of course sound. It’s well worth getting if you’re interested in the pre-war Tolkien, but be aware that there are huge gaps and elisions.

Some starting points on affectionate friendship in The Lord of the Rings

I’ve sometimes encountered comments from new readers of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, in regard to their surprise and even shock at the book’s rising level of male-male affection, kissing, expressions of love, and also the book’s general celebration of un-neurotic and un-conflicted male bonding. It may seem curious to today’s readers that Tolkien felt free to so boldly portray these aspects of Middle-Earth, and also to launch such books into the cultural and emotional ice-age of the 1950s.

Probably it has something to do with the period in which Tolkien came of age, roughly 1908-1922.

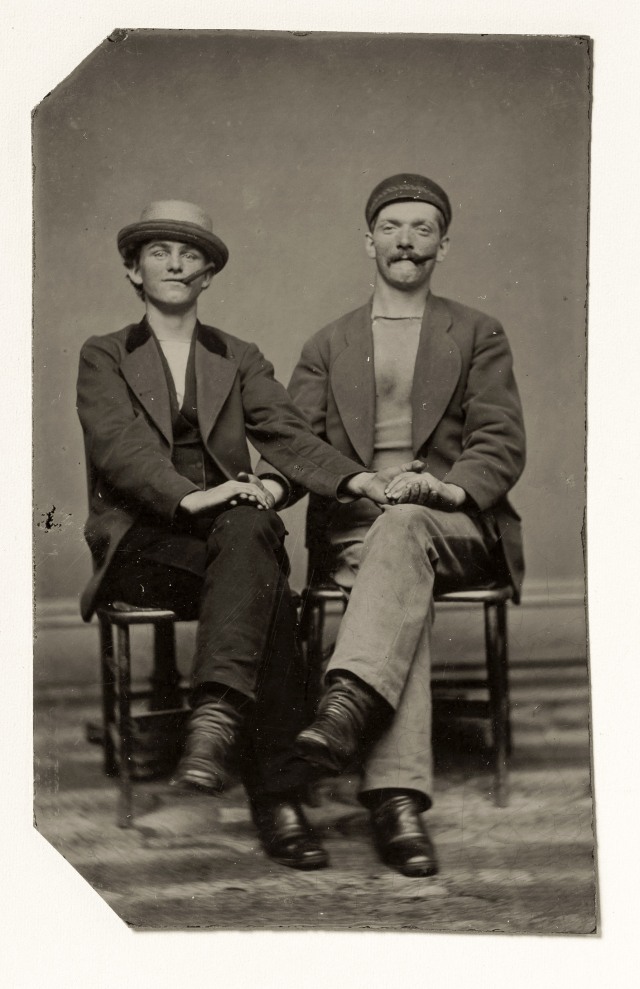

* Wilde and poetry. It was a post-Wilde world, in which previously open traditions of casual male-male affection in friendship (see above picture) were diminished and policed. But his youth was perhaps sufficiently distant from the immediate impact of the notorious Wilde trial, in time and also in space. He was coming of age in practical can-do Birmingham, rather than the overheated literary salons of London. One might perhaps also consider the ongoing impact of Whitman’s poetry among literary lads, in terms of celebrating affectionate male bonding in England at that time, though I don’t know offhand of any evidence that Tolkien thought highly of Whitman. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad seems likely to have had more impact in Britain, especially in the context of the First World War — when a copy was reputed to have been in almost every back-pack as our soldiers departed for the Front. For strong discussions of the war poetry and its portrayal of affectionate friendship in a post-Wilde context, one might look at Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature (2005) and the seminal The Great War and Modern Memory (1975). For the modern student, it’s perhaps important to highlight that poetry was then vastly more culturally important than it is today, and also engaged in a far more active dialogue with art.

* Freud. Doubtful. Tolkien lived in a pre-Freud world as he came of age. Freud only became widely known among the intelligentsia in the English-speaking world from about 1919, and even then he was usually encountered through a lens of superficial re-interpretations and even ‘progressive’ charlatans and quacks. The fathers of Tolkien’s Birmingham Oratory were Catholics of a variety who were fairly open to the world, by the standards of the time, but one has to doubt they had any regard for the likes of Freud and his followers. Still less would they have had an affection for Freud’s befuddled leftist acolytes — of the sort who drifted around Greenwich Village and Bloomsbury, revelling in a heavily sexualised home-brew made from half-fermented bits of Alder, Jung and Freud. The type later became academics and plagued Tolkien with their detested attempts at early ‘literary criticism’ of his work. It’s true that such ideas did become increasingly fashionable in England in the 1930s, and the writings of Freud’s associate Jung were known to some of Tolkien’s circle. But it would be a huge mistake to claim that Tolkien was juggling psychoanalytical ideas on male affection while devising The Lord of the Rings.

* Service. Far more important for understanding Tolkien’s main work seems to be the forgotten history of the entangling affections which can grow up in an enduring master-servant relationship. Also the traditions and set of implicit boundaries which develop from that, within a stable and self-confident civilisation. Then the ways in which that tradition fed into, and was changed by, the experience of the First World War and the ideological ferment of the 1930s.

* Fraternity and fellowship. There is also the little-regarded history of ‘public friendship’ to consider, in which affection became embedded and expressed in the brotherly networks of civil society and mutual aid, often along lines of civic/political affiliation. One could even see Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings as making an attempt at ‘working back’ to an idealised Christian form of this, as a reaction to the ‘politicised friendship’ developed by the proto-fascist left/right in Europe in the 1910s and 20s around hiking and the outdoors life, and which was later so ruinously militarised by the youth cadres of both national socialism and soviet socialism.

* Brotherly and knightly love. Asexual brotherly love and its traditions and standards within Christianity, would also prove a useful and fruitful line of enquiry. It was a strong tradition, in which gestures of love and affection were simply not culturally understood as diminishing one’s masculinity, or inviting an onlooker to cast aspersions about one’s innate erotic inclinations. The brotherly love tradition arose from The Bible’s examples, but was also deeply developed by the Christian monastic literary tradition which celebrated highly romanticised loving male friendships, often within a knightly tradition. On that, see Edward Joe Johnson, Once There Were Two True Friends, Or, The Idealized Male Friendship in in French Narrative from the Middle Ages Through the Enlightenment (Summa, 2003). I imagine that one may also be able to trace such ideas in Tolkien favourites such as the neo-medievalist fantasy novels of William Morris (there is no concrete evidence, but we can be almost certain he read House of the Wolfings, Roots of the Mountain, and Jason fairly early on).

* Within strands of old-school Catholicism there are said to be traditions of ‘spiritual friendships’, of ‘soul love’, related to the above.

My short and quick search for further print material reveals that the introductory book on ‘Loving asexual affection among male friends: a history’ has yet to be written. Many in our highly politicised Eng. Lit. depts. will think it enough to reflexively point the beginner to Sedgwick’s famous Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985). But that book assumes desire, and is now understood within a wider perspective which is very much entangled in discovering a history of casual gay sex and the wider project to back-date the modern post-1972 naffly rainbow-flagged gay identity.

A glance at the contents page for the book Sentimental Men: Masculinity and the Politics of Affect in American Culture (1999) suggests that none of the essays there are on-topic. The book The Overflowing of Friendship: love between men and the creation of the American republic (2009) looks much better. The British Empire and American ‘wild frontier’ experiences of male bonding are probably quite important in terms of feeding their structures of feeling through into the all-male ‘big landscape’ adventure novels of Tolkien’s youth (Henty etc). In that regard the article “Romantic friendship: male intimacy and middle-class youth in the northern United States, 1800-1900” (Journal of Social History, 1989) also looks like it might be a useful starting point.

The book Modernism, Male Friendship, and the First World War (Cambridge, 2003) is on the novelists Forster, Conrad and D.H. Lawrence and judging by Google Books it looks rather tedious (I was forced to read and study Lawrence and Forster at school, and as a consequence loathe both). But the book is on-topic in terms of the influence of the war and may prove to have some useful structuring ideas which are portable. But note that the author appears to come at this “neglected topic” via a modern leftist viewpoint, one which focusses on “institutional social power” and assumes “thwarted homoerotics”.

There is more to be found, lightly scattered among the Tolkien essays:

* Marion Perret, “Rings off their fingers: hands in The Lord of the Rings“, Ariel, Vol.6, No.4, 1975, pages 52-66. (Hands, fingers, touching are all recurring motifs in the book, and of course hands are an important means of conveying affection. Tolkien was also academically interested in the communicative role of hand gestures in combination with speech).

* Marion Zimmer Bradley, “Men, Halflings and Hero Worship”, in Tolkien and the Critics: Essays on J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, 1968.

* A. Smol, “”Oh… oh… Frodo!”: Readings of Male Intimacy in The Lord of the Rings“, MFS: Modern Fiction Studies, 2004.

* A. Smol, “Male Friendship in The Lord of the Rings: Medievalism, the First World War, and Contemporary Rewritings”, 2005. (Conference paper).

* Magnús Örn Þórðarson, The theme of friendship in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, 2012. (A short degree dissertation, in English).

New addition, June 2017: Kaufman, Roger: “The amplification and avoidance of homosexual love in the translation of Tolkien’s work from books to films”. In: Kapell and Pilkington (Eds.), The Fantastic Made Visible: Essays on the adaptation of science fiction and fantasy from page to screen, McFarland & Company, 2015.

This blog post is just my quick and rather flighty survey of the topic, a version of that undertaken for a friend, but it may help someone more interested than I am to get started on writing in-depth about the topic.

In the Potteries in the 1820s and 1840s

Two first-hand accounts of personal visits to the Potteries in the first half of the 19th century, extracted from books:

1823, letter to The Monthly Magazine:

“You pass, in two minutes, from a crowded street into a meadow or a corn-field; and, amidst shops and factories, you continually stumble upon what was not long since a farm-house, and which yet retains somewhat of its rural, cottage-like character, wholly distinct from that of the mercantile edifices which have sprung up around it. Figure to yourself a tract of country, the surface of which, cut, scarred, burnt, and ploughed up in every direction, displays a heterogeneous mass of hovels and palaces, farm houses and factories, chapels and churches, canals and coal-pits, corn-fields and brick-fields, gardens and furnaces, jumbled together in “most admired disorder,” and you will have a pretty correct idea of the Staffordshire potteries. Then pervade the space your fancy has thus pictured, with a suffocating smoke, vomited forth incessantly from innumerable fires, and the thing will be complete.

The people, however, who pass their lives amid this dingy atmosphere, this “palpable obscure,” this worse than Egyptian darkness, seem to experience no inconvenience from it; and, in fact, to be scarcely sensible of the existence of the evil. One of them asked me, with most amusing simplicity, “whether London was not a terribly smoky place to live in?” The inhabitants, nevertheless, I repeat, though not blessed with the rosy cheeks we generally see in country-folks, appear to enjoy good health, with the exception of the colliers [miners], and a few pallid mortals employed in the preparation of certain deleterious articles made use of in the manufacture of pottery.”

24th January 1850. Letter XXIX, given in the book The Victorian Working Class: Selections from Letters to the Morning Chronicle:

“As a whole, the appearance of considerable portions of the Pottery towns, is not very unlike that of the better parts of the iron and coal districts which I have described in the south of the county. The population, however, from the nature of their occupation, look clean and respectable. At meal times, or in the evening, they pour out from the manufactories — men, women, and children — with aprons and sleeves plentifully besprinkled with dashes as of liquid white clay. Here and there, however, you see a symptom of the neighbouring coal-mines, in the appearance of men and boys in coarse besmirched flannel clothing and wooden clogs, with faces and hands like [chimney] sweeps.”